The coal era is not coming to an end

When the Hazelwood power station shut last year the Australian Conservation Foundation claimed that its closure was a signal that “the era of polluting coal is coming to an end.”1

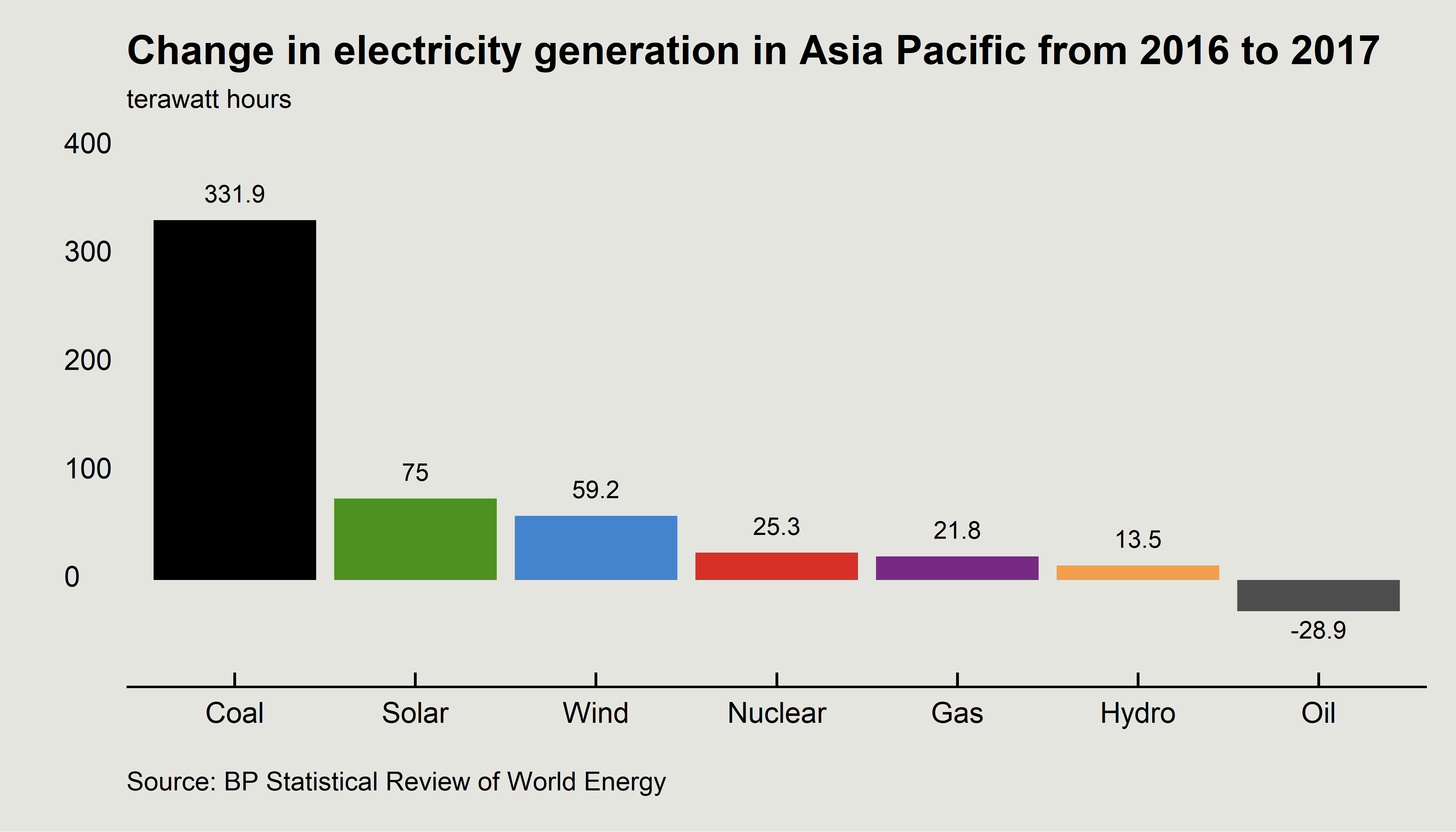

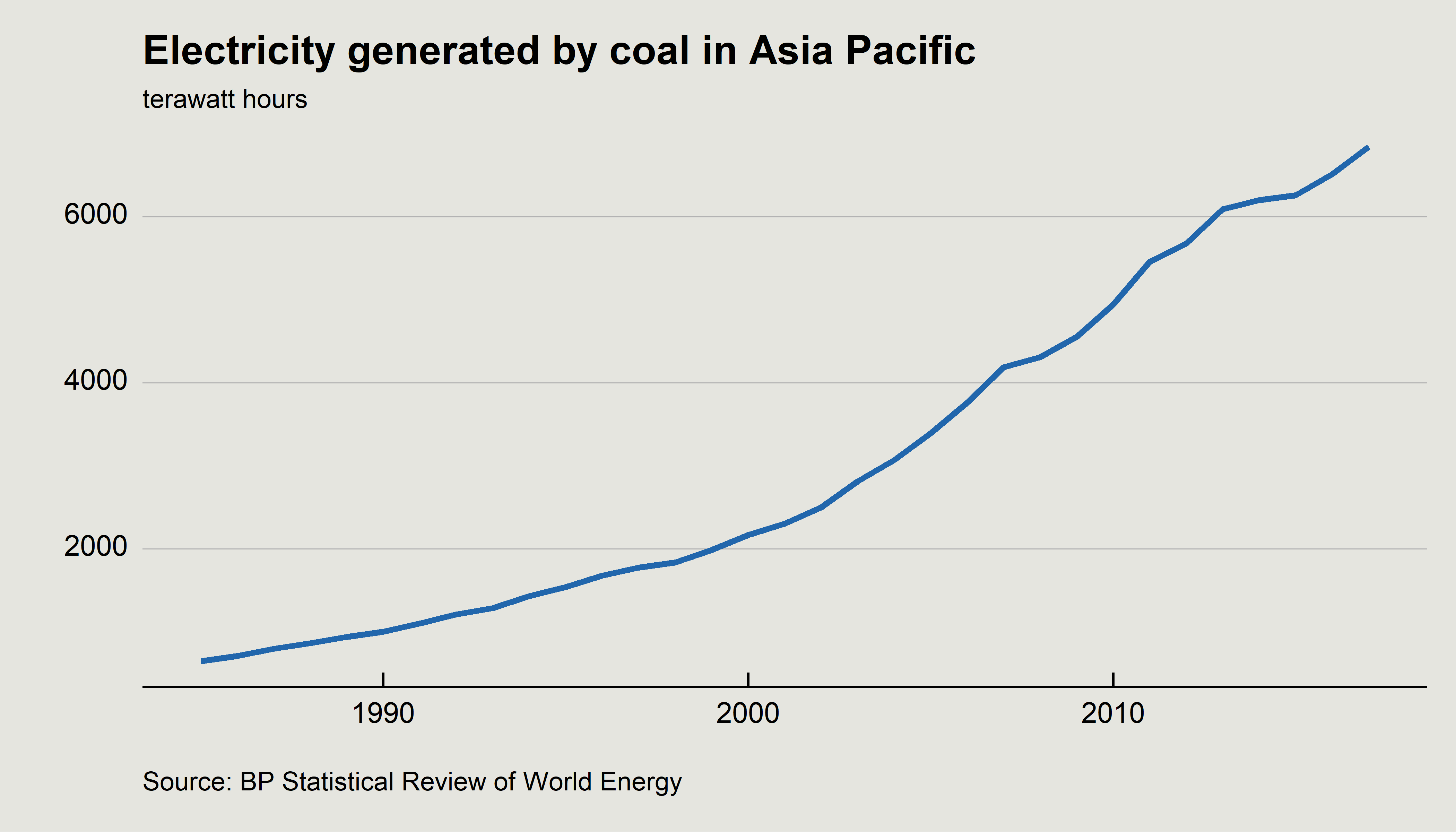

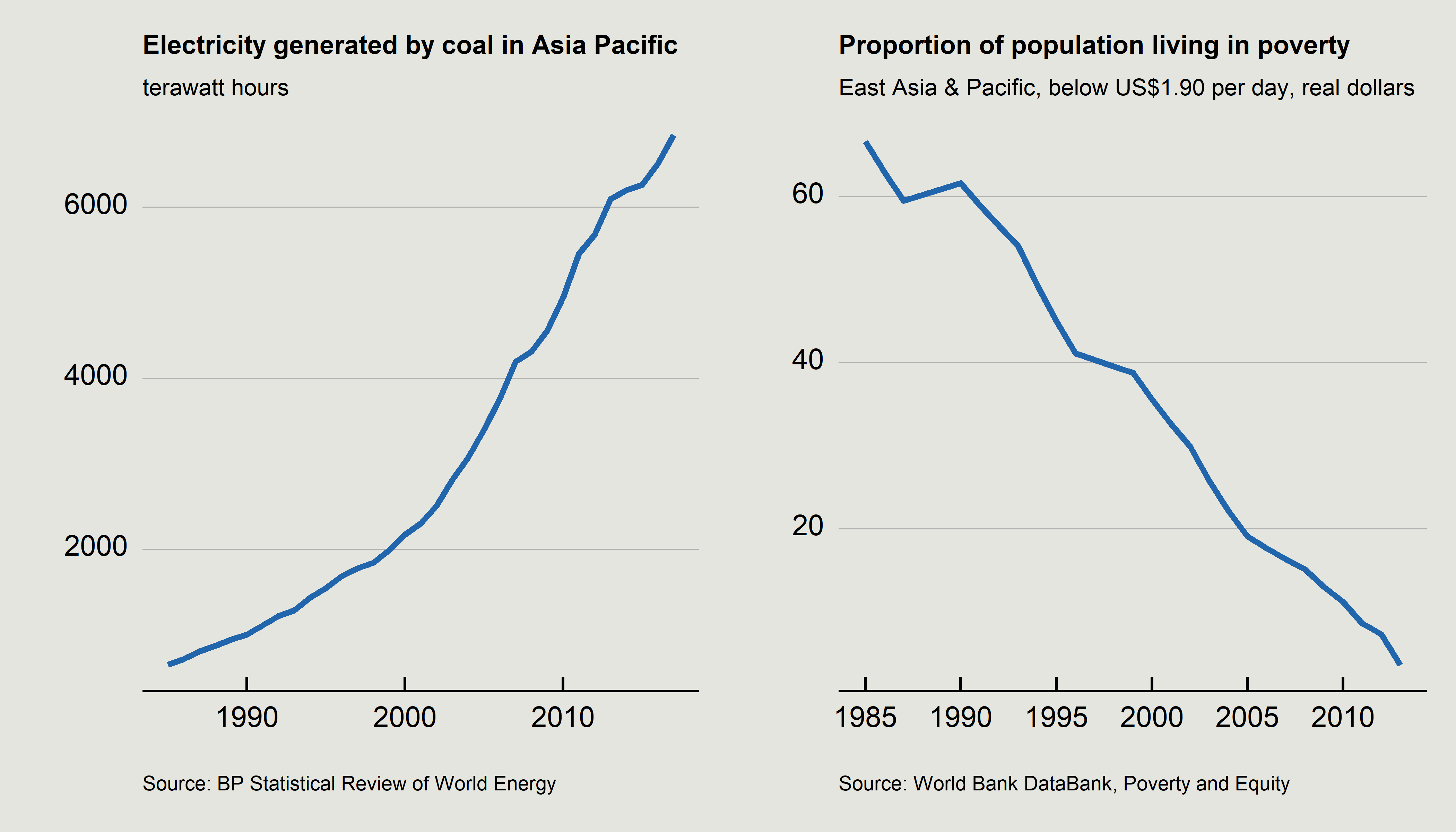

In its last full year of operation, the Hazelwood power station generated 10 terawatt hours of coal power.2 In the last year, coal fired power generation has increased in the Asia Pacific region by 330 terawatt hours. So, in effect, in just one year, the Asian region has brought online the equivalent of 33 Hazelwoods - while we shut one coal fired power station in Australia. So much for the era of coal coming to an end.

Last week, BP released its respected Statistical Review of World Energy. Its statistics show a resurgence in the growth of coal fired power after a few years of moderate decline. These declines had been heralded as the death of coal but clearly those claims were greatly exaggerated. In the last year electricity production in Asia increased by 500 terawatt hours and coal contributed two-thirds of this increase.

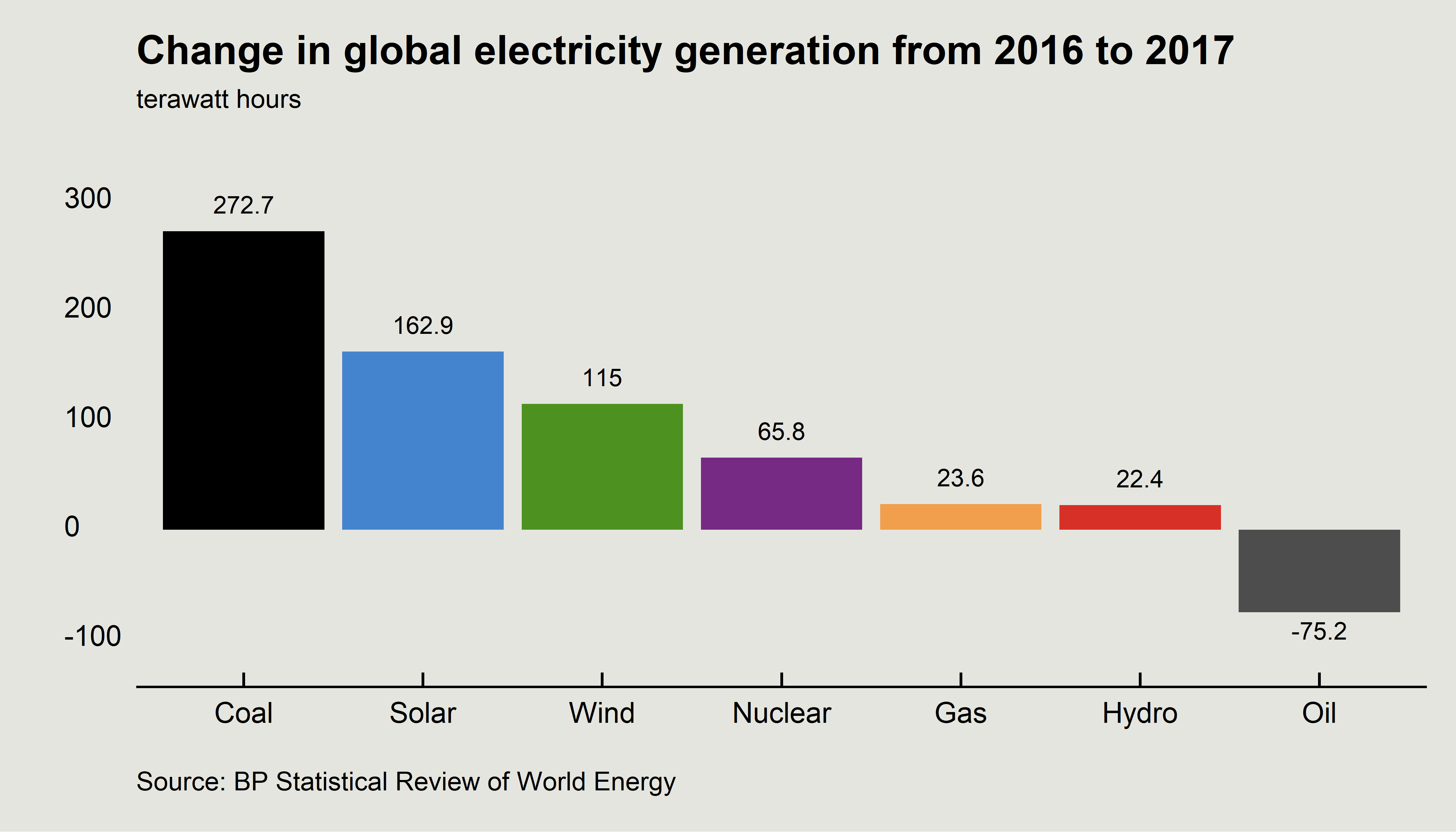

There has been strong growth in solar and wind energy sources too but these increases are much smaller than the contribution of coal. That is true when looking at the whole world too, not just the Asia Pacific region.

Global electricity production increased by over 600 terawatt hours in the past year, and just under 50 per cent of this increase was through the greater use of coal. There have been declines in the use of coal in the United States (because of cheap shale gas) and Europe (because of policy changes and natural depletion). However, the Asian region is what is relevant for our coal industry because that is where our exports are sent.

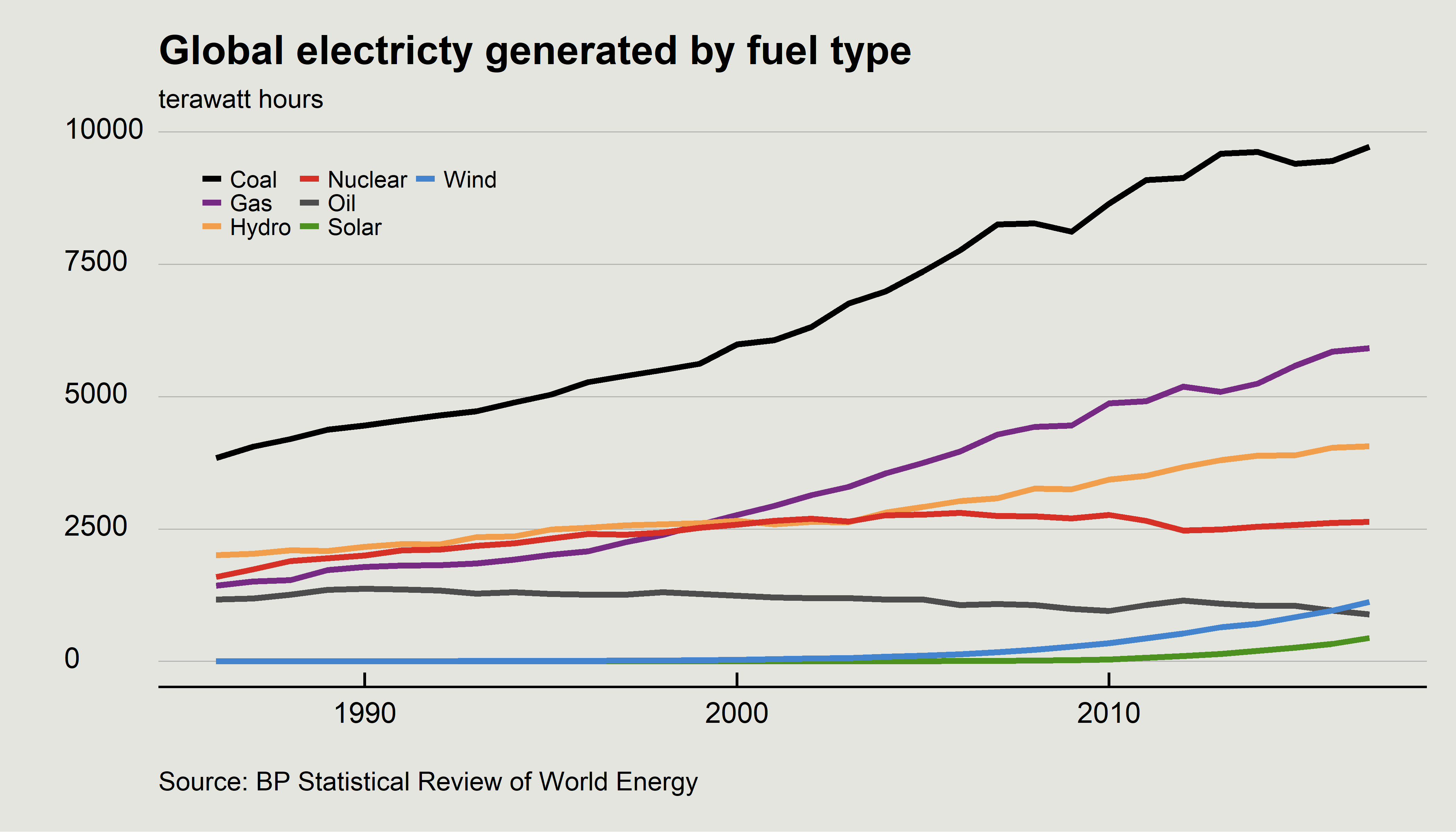

In 2017 coal fired power set a new record for supply at 9723 terawatt hours, representing 40 per cent of world electricity generation, and by far the largest single source of global electricity. The proportion of electricity supplied by coal has not changed in 40 years.

As BP’s Chief Economist said on the release of the statistics:

… despite the extraordinary growth in renewables in recent years, and the huge policy efforts to encourage a shift away from coal into cleaner, lower carbon fuels, there has been almost no improvement in the power sector fuel mix over the past 20 years. The share of coal in the power sector in 1998 was 38% – exactly the same as in 2017 … The share of non-fossil in 2017 is actually a little lower than it was 20 years ago, as the growth of renewables hasn’t offset the declining share of nuclear.3

In a major speech last year, the Labor party’s energy spokesperson, Mark Butler, claimed that “there is a clear structural shift underway in the global thermal coal market.”4 Numbers have never been the Labor party’s strong suit but this is taking doublespeak to a new level. Have a look at the graph below, which shows global electricity generation, and try to identify how you could describe that there is a “structural shift” away from coal fired power.

Coal fired electricity has increased by 62 per cent since 2000. It has been the fastest increase in coal use on record.

This trend is even starker in the Asia Pacific region. In the Asia-Pacific, coal power has more than tripled since 2000, and there is no sign of the increases reversing.

These increases can only but be the result of continued investment in coal fired power stations. Over the past 15 years more than 1000 GW of coal fired power has been built. To put that in context that is equivalent of over 600 Hazelwood power stations.

And the trend is not slowing down. In the last 5 years, China’s coal production capacity has increased by almost 300GW. In statistical terms, 3 new Hazelwood sized coal power plants have opened every month in China for the last 5 years.

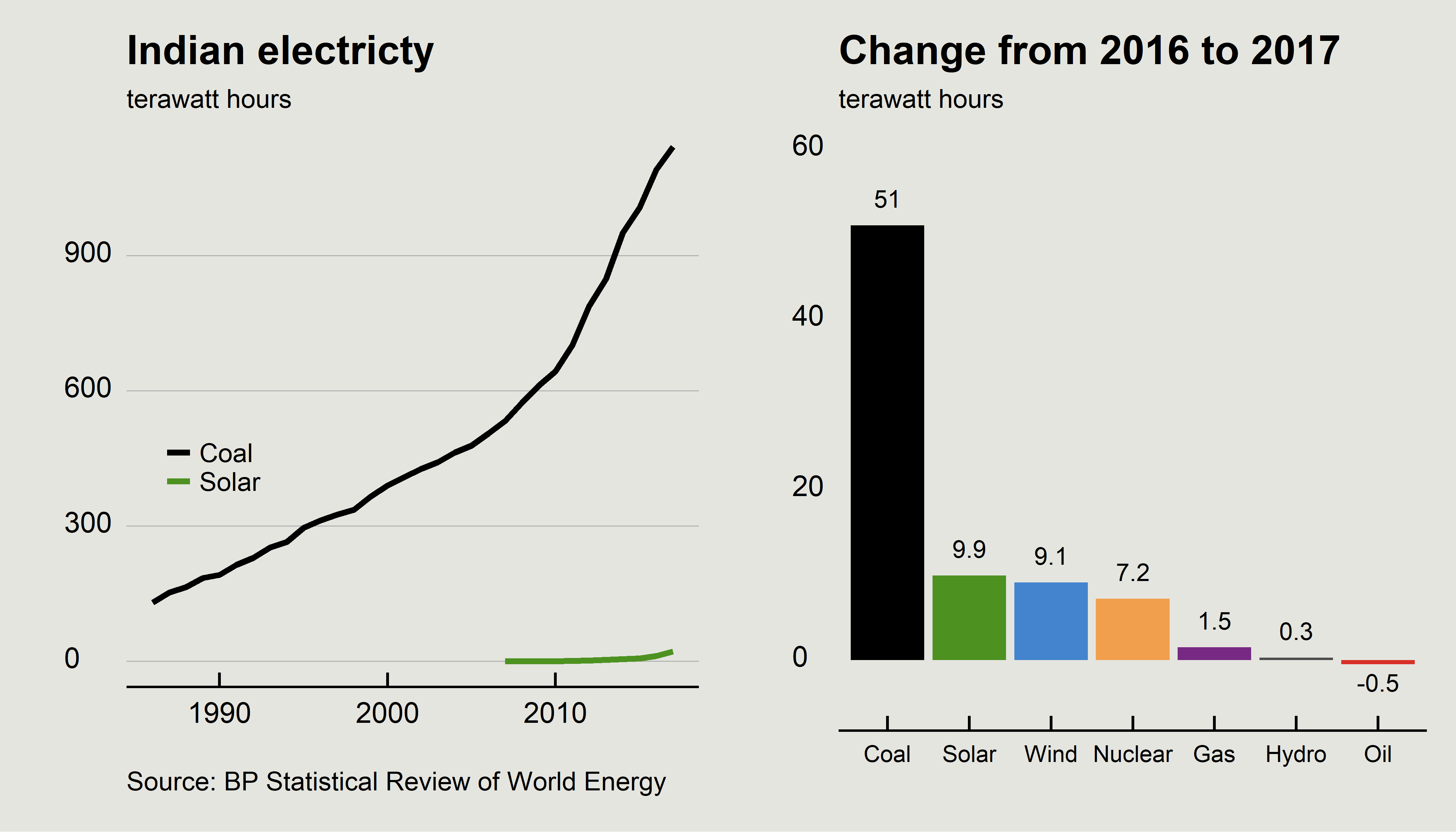

Environmental groups often claim that India can “skip” the coal phase in its economic development and go straight to solar. Delusional is too weak a word to describe such thinking. Solar is growing strongly in India but coal generates 53 times more power than solar in India. More importantly, over the past year Indian electricity demand grew by over 78 terawatt hours and increases in coal power contributed 65 per cent towards that increase.

The construction of these new coal fired power plants will underpin the demand for coal for decades to come, as the typical life of a coal fired power plant is 50 years. This is good news for Australia given that we are the world’s largest exporter of coal. Continuing strong demand for coal will help support our terms of trade, our prosperity and employment in our mining sector.

While Australia is the world’s largest exporter of coal we are not a major producer of coal. We only produce 5 per cent of the world’s thermal coal. We produce a high quality product that helps increase the performance of coal fired power stations. This performance boost is even greater in new coal fired power stations so the demand outlook for Australian coal is strong.

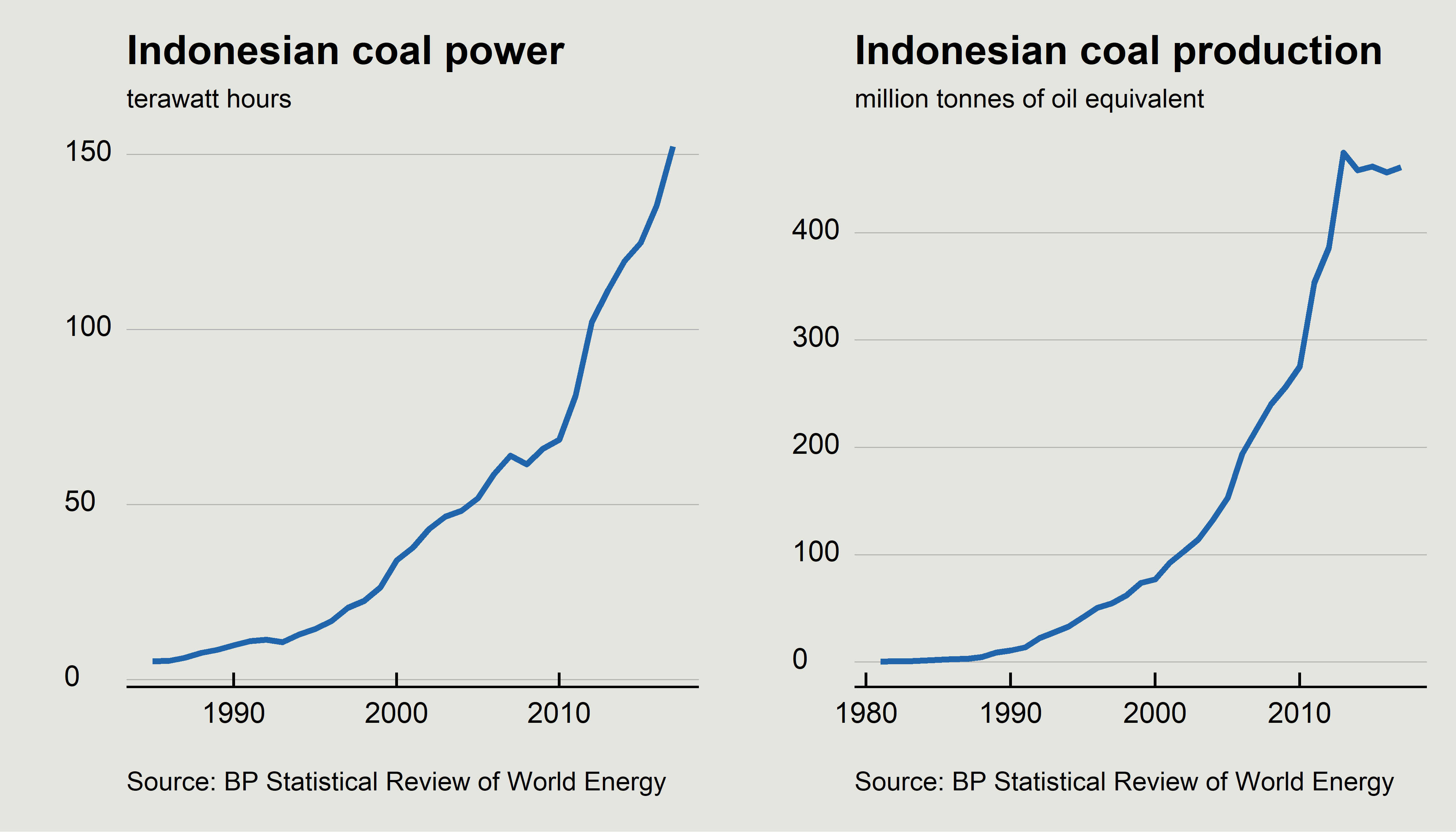

Australia’s major competitor in Asian coal markets is Indonesian coal. However, Indonesia is reserving more of its coal for its own needs as its domestic generation of coal fired power is growing significantly. Indonesian coal production has stagnated over the past few years and China has shut down some of its inefficient coal mines.

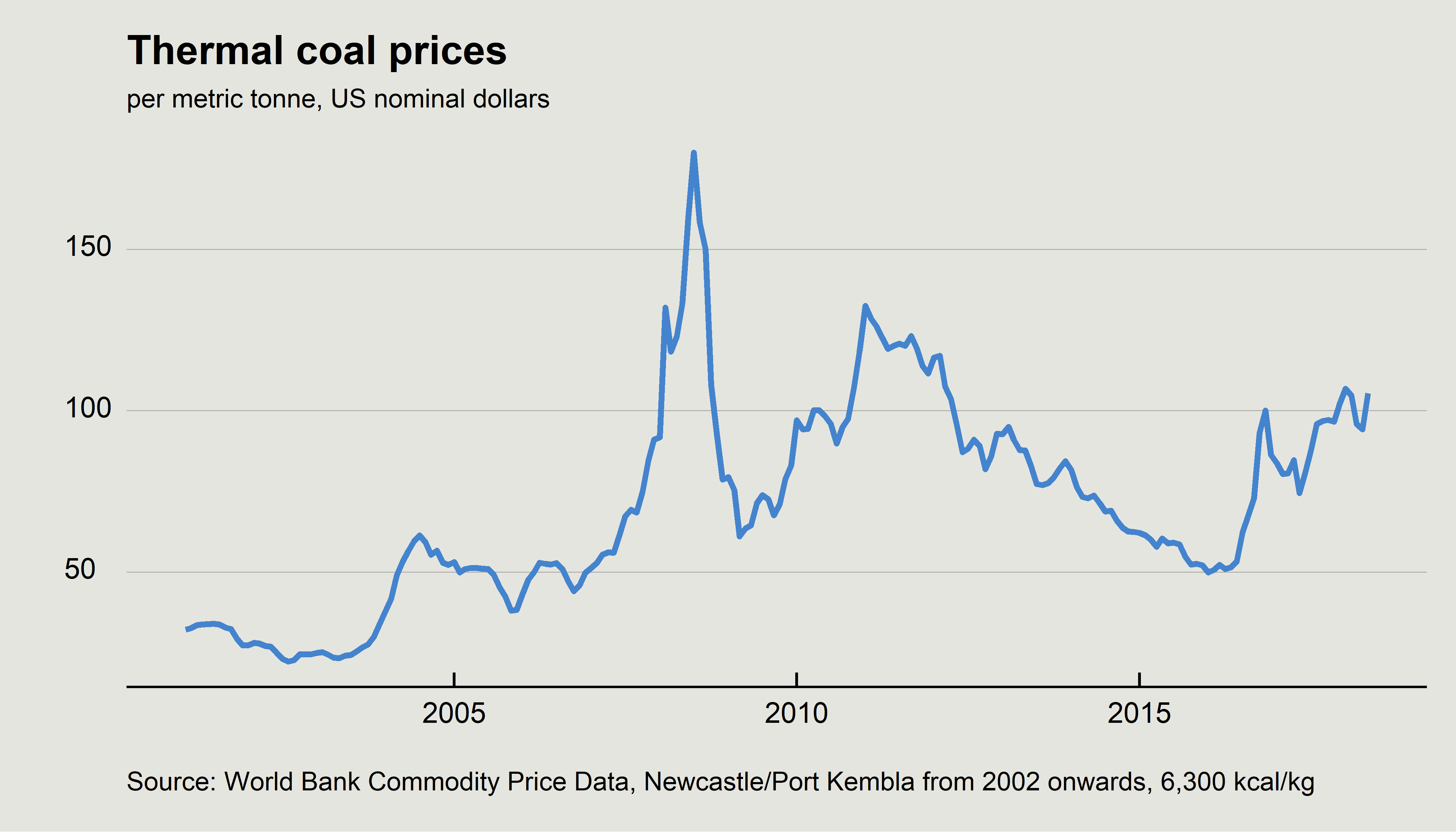

Higher demand and restricted supply have pushed up the price for Australian coal over the past two years. Two years ago coal prices had declined to pre-mining boom levels. Thermal coal prices have more than doubled in the past two years accordingly.

This buoyant market situation also makes it more likely that the Galilee Basin will be opened up and the Adani Carmichael coal mine (the first in the Galilee) will start. Financial analysts Wood Mackenzie estimate that the cost of coal from the Adani Carmichael coal mine will be about US$40 per tonne.5 The current coal price is over US$100 per tonne so that there is a strong commercial rationale to develop these supplies.

That would be great news for Australia. The Galilee would be the first major, new coal basin opened for more than 50 years. There are 5 other proposed mines in addition to Adani’s and altogether they would create more than 16,000 jobs.

The world is not short of coal, and if Australia does not increase its production, Asian countries will source coal from elsewhere. US coal exports to Asia more than doubled in 2017.6 Additional US coal exports to Asia are limited by the lack of bulk coal export facilities on the US west coast. However, there are 7 coal terminals proposed and combined they could handle over 125 million tonnes per year.

So far, Democrat state governments have prevented their construction. Earlier this year, Wyoming, Montana, Kansas, Utah, South Dakota, and Nebraska took Washington state to the federal court, arguing that the state’s rejection of coal exports was a restraint on their trade.7

Higher prices for coal reflect that coal is valued by the customer. Coal provides reliable and affordable energy and helps support the economic development of impoverished nations. It is good that Australia becomes more prosperous from the sale of coal. We do so because that sale creates value in another country. If you value the reduction of poverty and the economic development of poorer nations, the greater use of coal is a good sign. As coal use has increased by more than 6 times in the Asia Pacific region, poverty (as measured by those living on less than $1.90 per day) has been slashed by 95 per cent.

I hope that world poverty continues to fall. To do that energy use in poor countries will have to increase and it is almost certain that cheap and affordable coal fired power will be part of the equation. At the very least, poor countries should not allow rich countries to hypocritically lecture them that they should not use coal. Those same rich countries often themselves are rich thanks to the use of coal.

Last year, the United Kingdom and Canada launched the “Powering Past Coal Alliance”, which aims to convince countries to phase out coal. That’s right, the country that kicked off the Industrial Revolution through the use of coal, and has pretty much mined every tonne of coal from its small island, is now telling the poor countries of the world “do as we say, not as we do”. Who said the British Empire is finished?

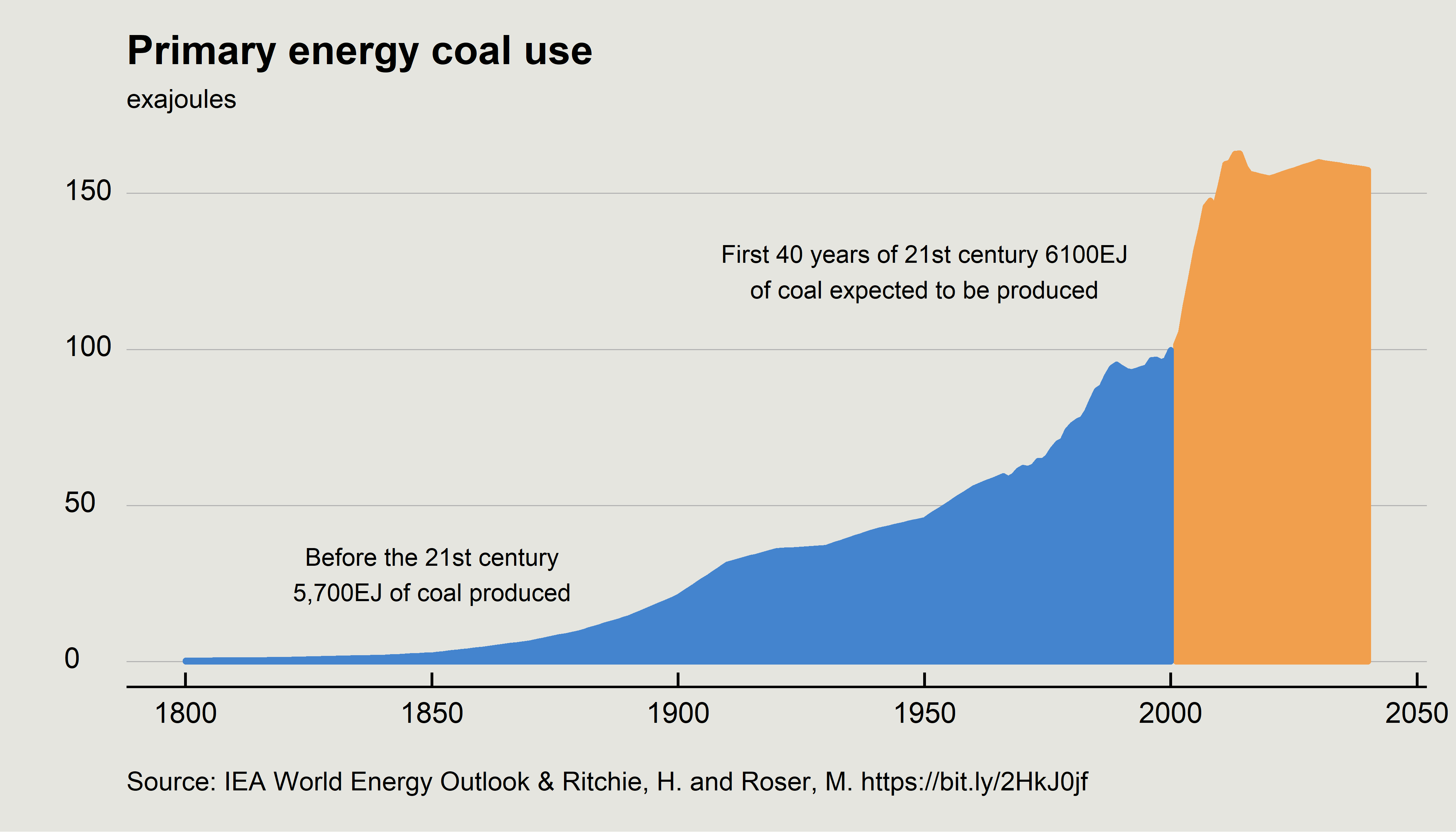

The world will need to produce as much coal for the first 40 years of the 21st century as we have in the whole of history before. The numbers are astounding. According to data compiled by Vaclav Smil, the world had produced 5,700 exajoules of coal from 1800 through to the year 2000. In the first 40 years of this century, the International Energy Agency estimates that the world will need almost 6,100 exajoules of coal.

This underlines the bright future for the Australian coal industry. The use of Australian coal is good for the world because it is cleaner, more efficient and helps promote economic development lifting millions of people from poverty. The era of coal is far from coming to an end.

ACF 2018, Hazelwood is closing, https://bit.ly/2MA99gn↩

AEMO 2018, Interactive Map, Historical Information, https://bit.ly/2HX0zof↩

BP 2018, Analysis – Spencer Dale, group chief economist, https://on.bp.com/2t0EFfh↩

Butler, M. 2018, “Managing Climate-Related Financial Risk - Lessons from Adani”, Speech to the Sydney Institute, 19 Feburary, https://bit.ly/2HV8uCw↩

Wood Mackenzie 2016, Carmichael coal mine, June.↩

EIA 2018, ‘U.S. coal exports increased by 61% in 2017 as exports to Asia more than doubled’, 19 April, https://bit.ly/2JNIz5B↩

Geiling, N. 2018, ‘6 states join battle over the largest proposed coal export terminal in the U.S.’, Think Progress, 14 May, https://bit.ly/2jWQZIw↩